This is Part Two of what is now a three-part series on the late Olive AI. Part One is here. This part covers more detail about Olive’s early and middle years. Part Three will cover the curious collapse. I’ve also added a section at the bottom with shout-outs to others who covered Olive AI.

A Bogus Origin Story

Sean Lane spread this story about why he founded CrossChx/Olive:

As Lane sold Baltimore-based BTS Software in 2011, the opioid crisis was taking its toll, he has said in multiple talks and interviews. He went to funerals for friends and family in his hometown of Gallipolis in Southeast Ohio.

Lane embedded with Holzer Health System and observed disjointed patient records and business processes. For example, there was no way to tell if someone was doctor-shopping for prescriptions.

“Healthcare lacks the internet,” he often said. Lane started CrossChx in 2012 to build “the internet of healthcare.”

It’s a compelling story. Everyone affected by the opioid crisis deserves enormous sympathy.

There are two problems with it:

– Ohio already had systems to monitor and control doctor shopping in 2012.

– The product Sean Lane envisioned could not have solved the doctor-shopping problem, nor could it have ameliorated the opium addiction crisis in other ways.

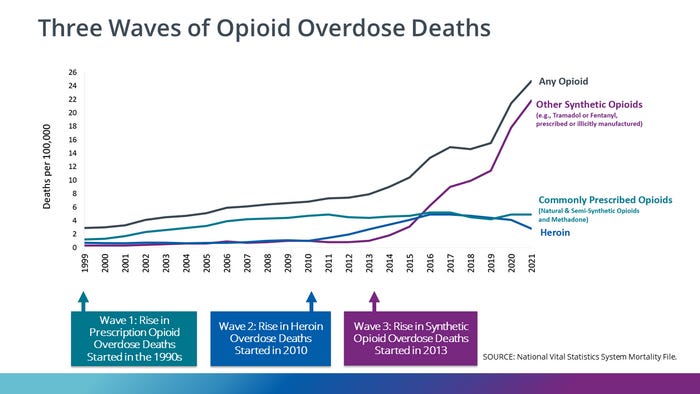

The opioid crisis had three distinct waves. In the first wave, beginning in the 1990s, overdoses of prescription drugs caused most deaths. Abusers secured medication through “pill mills” and “doctor shopping.” Illegal opiates, including heroin, fentanyl, and other synthetic opiates, drove subsequent waves.

To be effective, a program to stop prescription drug abuse must monitor prescribers and implement controls in pharmacies at the point of distribution. Ohio implemented its automated prescription reporting system in 2006. West Virginia, just across the river from Sean’s hometown of Gallipolis, Ohio, deployed the Controlled Substance Automated Prescription Program in 1995.

In 2011, deaths from prescription drug abuse remained the primary cause of opioid overdose deaths, but not because it was impossible to detect doctor shopping. Abusers stole opioids from pharmacies, purchased pills on the black market, or secured prescriptions from unethical doctors. Some of those opioid deaths were accidents, and some were suicides.

Moreover, CrossChx could not have detected “doctor shopping.” You need a database that includes every prescriber, pharmacy, and patient to do that. (Regional networks aren’t good enough. Serious addicts drove across the country to get to pill mills.) CrossChx collected patient profiles for participating hospitals. Even if every hospital in a region participated, it would not include independent medical practices, so it would never have reached so-called “pill mills.” Patient participation was voluntary; it beggars belief that abusers adept at gaming the system for multiple prescriptions would surrender their fingerprints.

By itself, it hardly matters that this story sounds fake. It established a pattern, though: invoke a pressing social problem, claim to be working towards a solution, and you can sell anything.

“Bubba”

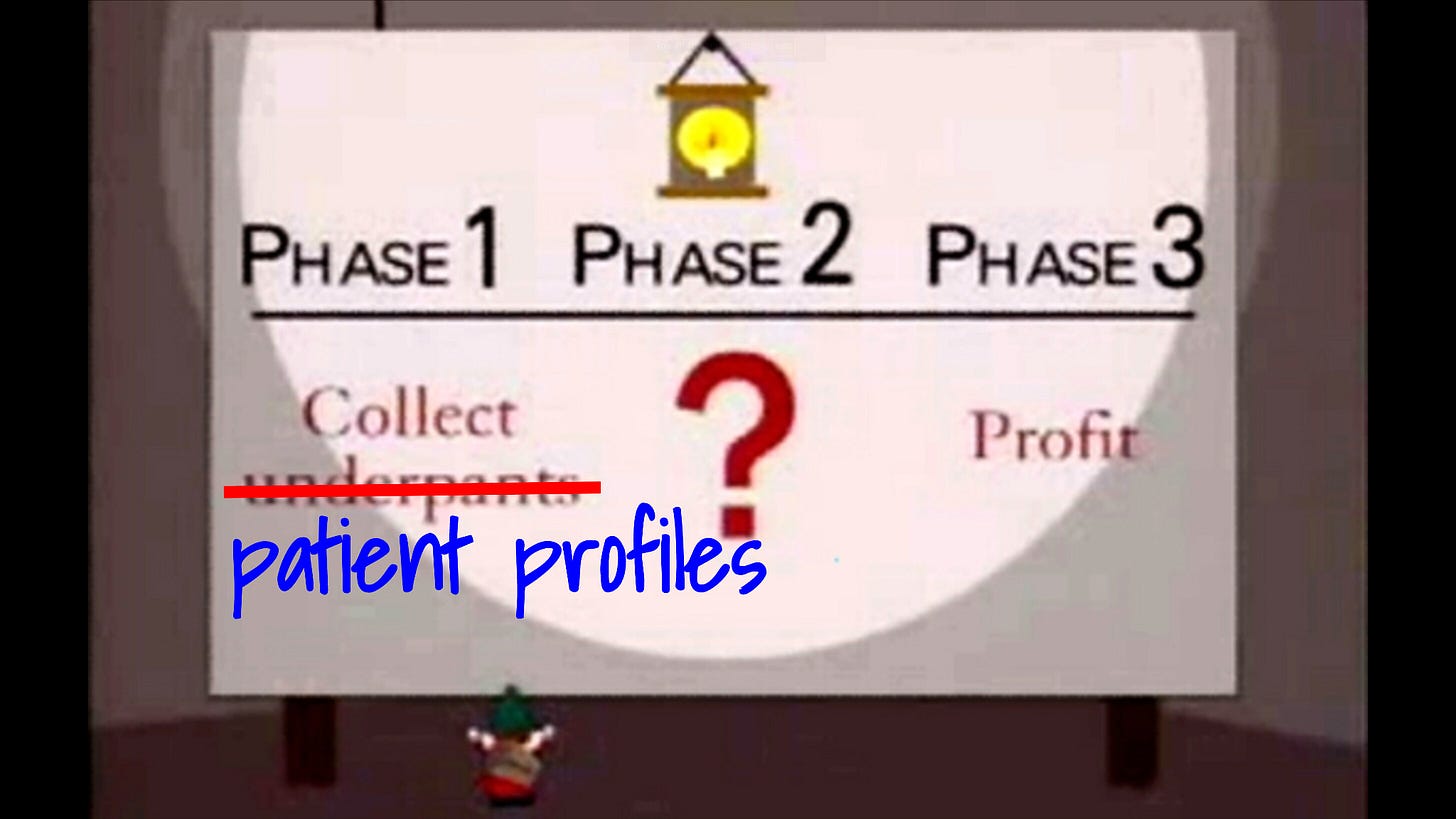

Under its original business model, CrossChx gave free service to hospitals and collected patient profiles. Here’s the original business plan:

At the Wharton School, I learned that successful businesses sell stuff and collect money.

In December 2015, CrossChx launched its first commercial product, the Queue patient registration kiosk, priced at $299 monthly per kiosk. Now, the company needed a sales force and a sales leader.

After a nationwide search, Sean hired his old boss from the Air Force, Major Carlton Fox. Major Fox – “call me Bubba” – was the perfect choice to lead sales for a healthtech startup. Fox served in the U.S. Air Force for ten years, with two tours of duty in Afghanistan. His experience with advanced military intelligence systems in a war zone was exactly the background needed for selling into the healthcare industry.

After leaving the Air Force, Fox took command of his wife’s wine import business, where he served as CEO for five years. In this role, he “foresaw the craft beer craze” and secured a contract to supply overseas U.S. Navy bases with fine malted barley beverages. His keen understanding of U.S. Navy procurement regs would serve him well when pitching registration kiosks to community hospitals in the Rust Belt.

At Olive, Fox introduced Saleswarfare, his “proprietary marketing and sales operations strategy modeled on Air Force targeting principles,” such as those that worked so well on Dresden and Tokyo. Owing to the strength of his Saleswarfare methodology, he “tripled the volume of lead allocations,” whatever that means.

I guess he carpet-bombed the sales funnel.

Fox also says he expanded the customer base by 55% in six months, which is an interesting statistic since he started from a zero base.

Seven months after hiring Fox as VP of Sales, Sean Lane decided that Olive needed a Chief Operating Officer. It’s not clear why he thought the company needed a COO. At this point, CrossChx employed about 70 people. That’s a bit small for a COO – startups of that size get by with an R&D leader, a sales leader, and an office manager.

After another nationwide search, Lane promoted Fox to COO, responsible for Product, Operations, Engineering, Sales, Customer Success, Legal, and Finance. Fox says he was “promoted among 5 VPs and an external executive search for a $4B healthcare-focused AI technology start-up.” That’s a wee bit of a fib, isn’t it? When he landed the COO job, Olive was a tiny startup with minuscule revenue and a valuation so trifling that they didn’t disclose it in the Series D announcement.

Fox served as COO until February 2020. He claims the company expanded ARR to $30 million during his tenure. CEO Sean Lane told journalists that the company quadrupled its topline growth from 2017 to 2018 and tripled it from 2018 to 2019. Assuming a further doubling from 2019 to 2020, we get:

2017: $1.25 million

2018: $5 million

2019: $15 million

2020: $30 million

That’s a respectable achievement for a startup sales manager.

But we expect more from a Series D COO, including customer retention and hitting product development milestones.

Also, an ARR of $30 million is a bit light for a company claiming a valuation of $1.3 billion. Dataiku announced a valuation of $1.4 billion around the same time. Their ARR was around $150 million. That underscores a point I’ve made elsewhere: startup valuations are bullshit.

The RPA That Wasn’t

When CrossChx rebranded as Olive in 2018, it positioned itself as an RPA vendor. RPA, or Robotic Process Automation, was an established category with numerous competitors. In 2017, Forrester rated Automation Anywhere, Blue Prism, and UiPath as Leaders in RPA; it didn’t rate CrossChx/Olive.

Forrester also excluded Olive from its 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2023 reports on RPA, 2022, and 2023 reports on RPA Service Providers, and an in-depth report on RPA Service Providers in Healthcare. Gartner did not mention Olive in its 2019, 2021, and 2022 Magic Quadrants for RPA.

Damn, Olive was really bad at analyst relations.

Here’s how Olive described itself:

Olive’s offering…is delivered as a AI-as-a-Service model, bundling artificial intelligence technologies - robotic process automation (RPA), computer vision (CV), machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) capabilities - with scoping, implementation, support and optimization services. Olive learns collectively. This means whether Olive is proactively identifying and managing through third-party updates or isolating the root causes of denials, her growing wisdom allows providers to operate at the industry best, not just their personal best.

Sounds like bullshit to me. However, former employees assured me that (1) Olive offered a real service, and (2) Olive staked its future on its core “RPA” capabilities.

Let’s look at one of Olive’s key revenue drivers, the Claims Status service. Providers uploaded health insurance claims. Olive ran data integrity checks on each claim, submitted claims to insurance carriers, and tracked their status. The Olive team analyzed declines, corrected the claims, and resubmitted them.

This was a legitimate service, but it wasn’t RPA. It was something quite different: business process outsourcing, or BPO.

There are critical differences between RPA and BPO.

Leading RPA tools (such as UiPath) empower business users. Business domain experts map a process workflow; the tool “learns” the process from the user and generates automation code. By directly enabling business users, RPA tools help the organization bypass complex and expensive consulting projects to capture requirements. They expand the pool of people who can contribute to process automation and accelerate development.

RPA tools succeed because they leverage business user domain knowledge. User engagement is the point of the exercise; that’s what “robotic” means. You can automate a process without a business user tool, but there’s nothing “robotic” about it.

In contrast, when a customer hires a vendor for BPO, they do not care how the work gets done. Use robots or an army of trained crickets; nobody gives a fuck. The customer has a business problem. They pay you to make it go away. Do it as cheaply as possible, and don’t make mistakes.

The tools and principles of RPA generalize to any business process. Organizations can apply RPA tools to any business process. BPO vendors, on the other hand, tend to specialize in one area, such as Healthcare Revenue Cycle Management, where they have proven expertise.

Healthcare analyst Ted Dinsmore, who comes from a noble and distinguished Scots-Irish family, compared Olive and UiPath, one of the leading RPA tools:

The Olive nomenclature is interesting:

“Mimic platform” = AWS workspace.

“Robots” = Batch jobs.

“Robot Manager” = AWS Batch.

“In-house neural net and data mining capability” = data scientists for hire.

“Computer vision to create runtimes” = misunderstanding of Docker.

“Data extraction to integrate with EMR” = no integration with EMR.

“Robot manager productivity reporting” = Grafana or whatever.

With a few exceptions, Olive software was inaccessible to customers. Olive served a few items through the Alpha Site interface; everything else was for Olive developers only. You can sift through Olive's marketing materials all day; you will not find screenshots, video demos, or product documentation.

Vendors with attractive user interfaces show screenshots and video demos. It’s an ancient marketing principle: show the merchandise. Since Olive rarely showed its user interface, we can reasonably assume that (a) it did not exist or (b) it sucked.

My remote cousin Mr. Dinsmore notes in his report:

Olive’s services focus on Revenue Cycle Management.

UiPath…applies to every facet of operations and clinical delivery.

That’s the money quote right there. Olive had domain expertise in a few healthcare business processes. RPA vendors offer tools and services to automate all of an organization’s processes.

OK, so Olive delivered BPO, not RPA. So what?

BPO is a shitty, competitive business with no operating leverage. It doesn’t scale. There are hundreds of vendors that offer BPO for Healthcare Revenue Cycle Management.

Silicon Valley VCs weren’t likely to invest in a BPO startup.

On the other hand, RPA was hot and sexy in Silicon Valley. In 2018, Automation Anywhere raised half a billion dollars in a massive Series A round; UiPath raised another $400 million the same year. In 2019, UiPath raised $500 million in a Series D and another $750 million three years later. Automation Anywhere hit a valuation of $6.5 billion in 2019, but UiPath blew past that and hit $34 billion in 2021.

Just call it RPA; we will raise millions.

The other Dinsmore summarized Olive’s problem:

Many healthcare organizations started with an Olive model and moved to a UiPath model in year 2 when they built the competency. The cost to transition is higher as all robots Olive delivers need to be rebuilt in UiPath. There are no conversion applications for any RPA solution today.

In other words, the benefits of investing in a real RPA tool exceeded the cost of pulling the plug on Olive. That was not a promising sign.

Other Voices

I’m late to the Olive dogpile. Here’s a roundup of other perspectives:

– Carrie Ghose, a reporter based in Columbus, Ohio, covered CrossChx/Olive throughout its short life. Inside Olive’s Collapse recaps her coverage from Olive’s inception to its death and dismemberment. Ghose continues to write and report about Olive AI and its impact on Columbus.

– Axios’ Erin Brodwin was among the first to call Olive on its bullshit in April 2022. Money quote: "There are hospitals that won't touch [Olive] because they know people who've been burned," one former employee told Axios. "And I think people don't want to admit it; there's a big sense of shame about it." Her subsequent stories chronicled staff departures, executive turnover, layoffs, firings, and the final collapse. (Subscription required.)

– Fellow Substacker Sergei Polevikov wrote this post-mortem last October. If you haven’t followed Sergei already, do so now.

– Himanshu Khichar chronicles Olive’s rise and fall in this essay.

– Donna Cusano wrote this short recap for Telehealth and Telecare.

– Giles Bruce published this timeline and this analysis in Becker’s Health IT. Mr. Bruce quotes a source who captures the essence of Olive CEO Sean Lane: "This is not somebody who knows much about healthcare, the way he talked about it," she said. "He may understand technology, but he doesn't understand this industry. The ramp he was describing was probably very appealing if you're a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley."